The Right to Be Disappointed

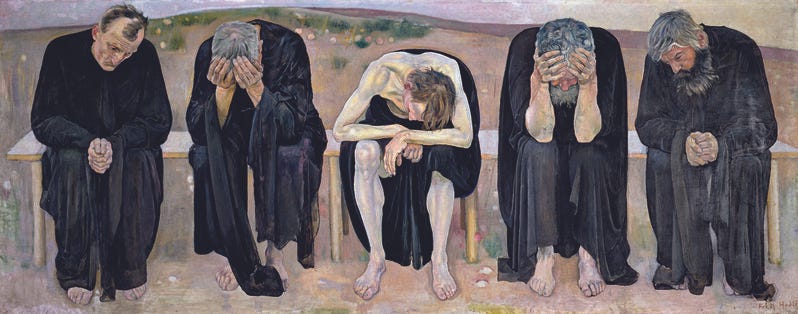

Ferdinand Hodler, “The Disappointed Souls [Les âmes déçues],” 1892

“I know you have been disappointed, Mr. Fitzgerald.”

“Disappointed!... Did you ever know any man who had so much right to be disappointed as I have?”

—Anthony Trollope, Can You Forgive Her?

Somewhere in between Providence and New Haven, the train must have slowed down. Absorbed in my book as I was, I didn’t notice the decrease in speed until the conductor’s voice came over the loudspeaker in the Quiet Car and said, folks, you might be wondering why we’re going so slowly. At that point during the trip from Boston to Washington, D.C., we were apparently supposed to be going a hundred miles an hour. We were not. He hoped that we hadn’t been disappointed.

There was, the conductor assured us, a good explanation for the temporary slow-down. They had received word—presumably from the local police—that there were two young men taking a walk down the middle of the train tracks. We would be going slowly for the next mile on their account so that, the conductor said, “their families’ Christmases won’t be ruined.” It being four days before Christmas, that made sense, except that it seemed to me that if the police were already aware of the pair walking down the center of the tracks, they would likely not still be on the tracks by the time that the train got to where they were. But no matter.

Was I disappointed by the fact that the train was going so slowly? No. I was not. I did not hold Amtrak responsible for the judgment of persons who, upon facing the dilemma of having to choose a walking route, had apparently chosen the nearest train tracks. And having had no specific knowledge pertaining to the proper speed of the train on that particular leg of the trip prior to the conductor’s mention of it, I had no high expectations on this point. Indeed, while I harbored some less than confident expectation that the train should arrive at Union Station on time or close to it, I lacked any specific hopes at all concerning the issue of speed, though of course, had I chosen to think through the matter, which I did not, again, due to absorption in my book, I would have realized that the speed of the train and the time of arrival at our destination were not unrelated. In the absence of hope, there was nothing to be dashed, for disappointment depends upon and is relative to the state of expectation that is its condition.

Dashed hopes—thwarted expectations—a fall from a real or imagined height, some present or future apparent good damaged or snuffed out in advance of its attainment: these are the stuff of disappointment. It arises from a breach between what it is reached for and what is grasped. That breach reveals the distance between imagination and reality. It teaches us that what we thought to be the case was not in fact the case at all, or that the role we imagined ourselves to be playing was just that—a role, and that we could be cast in another role at a moment’s notice.

When one has, at last, or all of the sudden, been duly appointed to some desired role by the presiding powers that be, one may feel oddly unmoved. The conferral of honor may feel redundant—a bit of a letdown. For it is the imagination that first appoints us to our desired roles in our own minds. With occasionally ludicrous extravagance, we imagine ourselves hired, honored, recognized, or rewarded—in short, appointed: given access to some place of high rank, whether figurative or literal. The dream of lofty office may be rewarding only until that office is actually attained and then again after that office, once gained, has ultimately been lost.

If, as it turns out, one fails to achieve high rank through accomplishment, one can at least associate oneself with it by virtue of proximity. I recall, for example, reading a wedding announcement in which it was noted that the bride and groom would spend their honeymoon on a beach that had been rated number one in a list of the world’s most beautiful beaches. But most of us go to beaches that do not warrant any special title, and some of us, alas, go to beaches that are known for things like an abundance of stinging black flies or, worse, discarded syringes that have floated up from New York (such for example, is the fate of one beach on Martha’s Vineyard that I remember from childhood). We inhabit places that are not Number One. In ripping the crowns off our heads, and relegating us to less highly rated—or worse, entirely unrated—destinations and positions, reality lets us down.

A discrete disappointment, if great enough, may well tip a person into desolation, despair or grief. But unlike these states, disappointment does not tend to take on the all-inclusive dimensions of an encircling atmosphere, as does, for instance, a driving blizzard. When a hope falls to the ground it may make a pothole or a sinkhole. Disappointment is the hole itself rather than the ground below the ground at the bottom of that hole. The ground below the ground is grief.

Grief may seem perpetual because sourceless, sizeless, and of unfathomable depth—yet somehow endlessly expansive—or orphaned, as in Richard II, Shakespeare’s greatest play about grief. Therein the king remarks that “Nothing hath begot my something grief / Or something hath, the nothing that I grieve.” In contrast, disappointment generally has a pretty good idea—however baseless or unjust it might be—of who or what brought it about; it does not lack for names of potential miscreants or means of casting blame on them.

Disappointment does not say: “I have a grief, but can’t tell where it is or how much.” It allows for qualifiers regarding its scope ranging from mild to great. To make these qualifiers explicable, it prompts the spinning of skeins of narrative detail: “The large turnips and swedes are much injured, the smaller ones may produce some greens; but this failure of roots has greatly disappointed the hopes of the farmers in helping out winter provender.” This makes sense. Yet narrative detail pertaining to disappointment does not always rest on such a solid basis. With respect to the following, for instance, we would likely strenuously reject on moral grounds the notion that single newcomers to a community should avoid being over forty, poor, or both: “[They] were pleasantly interested to learn that he was unmarried, and mildly disappointed at hearing of his poverty and forty years.” While we can’t share the mild disappointment, we can accept that this was likely a non-controversial reaction to the poverty and middle-agedness of a potential suitor in nineteenth-century popular short fiction.

Most commonly, disappointment tends to mean something like, “I hoped for X, and X did not come at all or came and I ruined it or came but was entirely other than the thing/person that/whom I had sought while hoping. My hopes were revealed to be false, unsustainable, or simply unrealizable, however beautiful. Now I am undeceived or disenchanted but deprived because of it, with no apparent means of consolation other than ones that will themselves disappoint.”

What was the last time you disappointed someone—perhaps in some small way that despite its seeming triviality may stay with them always? Before we get to that, when were you last disappointed and by whom or what? In that instance, were you right to be disappointed? Would you go so far as to say that you had “a right to” be? Perhaps you are so perpetually in a state of disappointment that it is impossible to say. Or maybe you take it as a given that you, like everyone else, are if not already disappointed then on the brink of being so. Life, friends, may well be disappointing, even if that disappointment is “meaningful”—meaning what? That we think it might be overcome or corrected or at least understood? In saying so, are we saying something other than “it is what it is” and thus that “it” is implicitly not what it ought to be? Has it always been this way? If so, what changed?

Disappointment and Dust

If someone in the ancient world disappointed anyone else, or suffered disappointment themselves, in the exact sense in we have discussed, they conceived of it differently and used some other word for it, suggestive, for instance, of having been abandoned or deceived. They knew about the dangers of hope. The Stoic Hecato, as reported by Seneca, said “Cease to hope and you will cease to fear,” and, Seneca adds, “Widely different [as fear and hope] are, the two of them march in unison like a prisoner and the escort he is handcuffed to.” The task, as he understood it, was to avoid projecting our thoughts into the future, and choose instead to focus on the present.

The lack of words in ancient languages the meaning of which would be exactly equivalent to contemporary notions of disappointment has not stopped translators or interpreters from thinking about and even referring to ancient disappointments. No survey of those disappointments will be attempted here. I would, however, suggest that, broadly speaking, if there is one lesson concerning disappointment to be taken away from the ancient world it is that remembering that you are going to die is the best way both to explain the inevitability of disappointment and to guard against it.

In the world of the Hebrew Bible, disappointment, grief, and sorrow of every variety may be traced to the same source: Adam and Eve’s disobedience in the garden. The bad news is that frustration and disappointment follow from the divine punishment meted out to the pair. Nothing is going to come easily. Adam is going to have to work for his bread by the sweat of his brow; Eve will suffer in bearing children. The good news, however, is that contra to God’s initial warning in Genesis 2:17 concerning the consumption of fruit from the Tree of Life that (“in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die”), the couple, as the story has it, goes on living well past that day, albeit in a postlapsarian world permeated with sorrow and loss. Disappointment, in this worldview, is, if not preventable, at least readily explicable. Fallen hopes are the hallmark of a fallen world.

In turning to the treatment of death and disappointment in Roman philosophy, one finds again the proverbial notion, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia, of the trajectory from “dust to dust” as the arc of human life. For the Stoic Marcus Aurelius, disappointment is not explained with reference to a mythic narrative of human origin, as in Genesis, but rather accounted for as everything else is accounted for, namely, with reference to the all-inclusive, mysterious category of what happens to everyone, whether they are good or bad. Everything must be accepted. Of course, some things are harder to accept than others, such as disappointments. But if one contemplates the journey from “dust to dust” one may see how useless and foolish it is to fret at the inevitable dispersal of one’s body into undifferentiated particles. It will pass, and quickly.

Epictetus makes the point concerning the calm that should follow from the contemplation of death explicitly in his Enchiridion: “Keep before your eyes day by day death and exile, and everything that seems terrible, but most of all death; and then you will never have any abject thought, nor will you yearn for anything beyond measure.” Keeping death in mind will prevent you from hoping for too much from life, the value of which is overrated. Worldly possessions may be stolen or broken, and even the most wonderful of experiences lasts but a moment. If you hope only according to the small measure appropriate to a short, brutal life you will not be greatly disappointed. Death is coming; it is common to everyone. There is no point in hoping to delay it, and no reason why any one death should be seen as more special than another. As such, we can see why Stoicism has no room for the idea of individual martyrdom that one finds both in Rabbinic Judaism and in Early Christianity.

Unsurprisingly, both Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus criticize the manner in which Christians attain indifference to death, as evidenced in their willingness to become martyrs. They welcome death not as a result of the dignified exercise of reason concerning the nature of the universe, as do the Stoics, but rather through a sort of “madness,” as well as habituation in Christian practice.

One finds the tension between Stoic and Christian perspectives on death not only in antiquity but in early modernity as well, particularly in Hamlet, that most Senecan of Shakespearean tragedies. In that play we find the first and only usage of the word “disappointed” in the entire corpus of the plays. In Hamlet, death is common, as in Stoicism, and special, as in Christianity. And the idea of “dust to dust” is as evocative of a seemingly secular and jocular notion of nothingness as it is of divine craftsmanship, providence, or justice.

The one person in Shakespeare’s world who is disappointed when his hopes are dashed is dead. More specifically, he is a ghost returned to earth to speak to his son about the fact that he was murdered by his brother Claudius while he was still in a state of sin and thus entered the afterlife in a state of inadequate preparation. Claudius, stained with the mortal sin that he incurred in poisoning his brother the king, and having abstained from the appointments through which he could have been absolved, is not ready to assume the role of resident of heaven. Instead, he has the task of roaming about, trying to spur the living into carrying out the task of cleaning up old messes on earth:

Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother's hand

Of life, of crown, of queen, at once dispatch'd;

Cut off even in the blossoms of my sin,

Unhous'led, disappointed, unanel'd,

No reckoning made, but sent to my account

With all my imperfections on my head.

Disappointment keeps the ghost of Hamlet’s father ground-bound, tethered to the business of being partly dust rather than purely spirit.

Act 5 in Hamlet stresses that everything human—no matter how glorious—is slated to return to dust in the end. The persistent undertow of this plodding, inexorable eventuality can be felt throughout Hamlet. In Act 1, when Gertrude instructs Hamlet that he should “not for ever with thy vailed lids / Seek for thy noble father in the dust,” her reason is that he should know better. Everyone dies; that is just the way things are. “Thou know’st ‘tis common. All that lives must die/ Passing through nature to eternity.” Hamlet acknowledges the accuracy of this truism; at this point in the play, he cannot offer any adequate rejoinder either to Gertrude’s comment or Claudius’s redundant observation that the “common theme” of nature is “death of fathers.” The commonness of death (a Stoic trope) means that entrance into “the undiscovered country” is not necessarily the fruit of a daring expedition of discovery. It is more likely the consequence of a routine expulsion to another land:

Gravedigger: (sings)

But age with his stealing steps

Hath clawed me in his clutch,

And hath shipped me into the land,

As if I had never been such.

[Throws up a skull.]

Hamlet: That skull had a tongue in it, and could sing once. How the

knave jowls it to the ground, as if 'twere Cain's jawbone, that

did the first murther! [5.1.66-73 ]

Whatever the disparate fates of their souls might be, the skulls of the innocent and the guilty alike end up in the same place. The sovereignty of dust lends democracy to death, as least as far as natural bodies are concerned. At that point, no ridiculous illusions of some people having rarer blood than others remain. Everyone is made of the same equally humble stuff and serves the same low purposes, regardless of what their high appointments might have been in life.

If we take secret comfort in the hope that nature buries and forgets our foul deeds, we may be disappointed in the fact that it forgets our personalities and accomplishments and indeed, our very existence as well. Were not our rises and falls governed by special providence? If there is special providence in the fall of a sparrow, that is very moving and morally attractive, but it means that providence is not reserved for human beings. Shakespeare presents us with two rival and equally extreme understandings of mortality: either all lives and deaths (including those of animals) are special or none are.

In Act 1, Hamlet can only answer Gertrude’s question to him about his father’ death—“Why seems it so particular with thee?”—by pointing to something particular about himself, rather than something particularly special feature of his father’s death. But when Hamlet hears from Horatio that his father’s ghost has been seen in arms, he immediately conceives of the episode in terms of justice, implicitly questioning the capacity of the ground to swallow up innocence and guilt alike. Only the foul deeds, he suggests, will rise; the innocent or good ones stay buried.

Recall that in the King James Version of the book of Genesis, dust is the medium for divine creation as well as divine justice. Human beings are made out of the dust of the ground (2:7); they are his creation. Alive, Adam and Eve are merely animated dust; once dead, they will return to the ground out which they were made. Cain kills Abel in 4:8. In 4:9, God shows up to question the murderer about his crime. Justice does not brook delay. The audible blood of the innocent itself cries out immediately to God for redress from the ground into which it has been spilt. Dust will not offer sanctuary to criminals by hiding the innocent blood that they shed.

By the time the notion that human beings are made out of dust shows up in Shakespeare’s Hamlet approximately one thousand years later, it is still tethered to ideas about justice, but along very different lines. In this context, the spilt blood of Hamlet’s father, the late king does not cry out from the ground and rise up (by means of sound) to be redressed. Human speech and action are required for justice, and justice means bloody revenge of the sort familiar to us from Senecan tragedy. Further, the story of Hamlet’s tortuous path to becoming an avenger takes a long time to unfold, and its unfolding must be spoken about to the otherwise “unknowing world” by Horatio. Horatio is to speak “Of carnal, bloody, and unnatural acts, / Of accidental judgments, casual slaughters, / Of deaths put on by cunning and forced cause, / And, in this upshot, purposes mistook / Fall’n on the inventors’ heads.” Once people have heard of such things, however, they may be forgotten or willfully ignored.

Hamlet evokes the ancient world, in which “Foul deeds will rise, / Though all the earth o’erwhelm them, to men's eyes.” This means that moral satisfaction is assured. Justice will be done—in time, yes, but it will be done. Yet moral disappointment of a modern sort also looms large in the play. Distraction and immersion in one’s own affairs prevail because people are not particularly disposed to pay attention. When the ghost of the murdered man shows up, his appearance is initially treated as the product of fantasy.

Hamlet is grieved by his father’s murder, and disgusted by his mother’s marriage to Claudius. Toward himself, however, he seems to feel something anticipatory of modern disappointment, with its emphasis on failed hopes and its endless capacity for dwelling on its own causes and effects. He worries that he does not feel passionately enough—he is not even as passionate as the visiting actor in a play who weeps over the fictive death of Hecuba. Having hoped to become a successful avenger—a “scourge of heaven”—he becomes instead a common murderer. But his feeling does not yet have the name of disappointment.

In modern life, as distinguished from tragic drama, disappointed people do not end up not in heaps of poisoned and stabbed bodies near former rivals speaking eloquently of the dead’s lost potential as rulers. Rather, they may end up in bars. Sitting on their stools, disappointed people, while drinking, may speak with one another about how awful some people and recent events are and, increasingly, as the evening goes on, of old, still partially inflamed and flammable injuries. Such persons don’t need to say anything; the way that they hold themselves tells us of their disappointments without needing to fill us in on what prompted them.

It would be obscene to say that people who are regularly subject to torture, extreme violence, or abjection are “disappointed.” The word has a silent “merely” in front of it. To be disappointed means first, that you had some sense of having been “appointed” to—hence, chosen for—something). This implies the existence of a functioning social architecture of choice: an order sufficient to support appointments. If you are disappointed, you may consider yourself fortunate: it means that you still have some expectations left that are of a sufficient weight and height to fall.

How Disappointment Became Modern

Modern people breed disappointment, possessed as we are of 1) high expectations that serve as radar to detect disappointment; 2) a tacit, often unaccounted belief that we have a “right to be disappointed” once it has been detected; and 3) a completely subjective yardstick for determining the grounds of disappointment. In current usage, disappointment is less commonly understood as a way of life than as a feeling that follows from an event or an event that gives rise to a feeling. The two dimensions of disappointment are closely linked. One gives rise to the other to the point one might say either “I was disappointed by the movie that won so many awards” or “The movie that won so many awards was a disappointment” and it would not make any difference.

It was not until the 14th century that one could be said to be “disappointed,” but at that time, it meant to have been subjected to a particular experience—one that did not necessarily beget feelings of disappointment. Disappointment began its career in French, as an event. To “dis-appoint” was to remove someone from an appointment that he had held, for example, the office of bailiff. If you could be appointed to an office, you could be dis-appointed as well. Offices of evil, as well as those of good could be vacated in this manner. Thus, one finds, for example, in sixteenth-century vernacular translations of the bible that God disappoints the wicked in their plans.

Modernity means, among other things, that “office-holding” is not regarded as a state peculiar to a few elect. Rather, some offices are everyone’s responsibility, and a privilege as well. Are we not all, for example, more commonly imagined to be “stewards” of the environment, as distinguished from “servants” of it? Is not “citizen of the world” a sort of moral office with attendant duties? The notable thing about these “offices” is that unlike formally or legally conferred offices, we cannot be “dis-appointed” from them. They are thought to be morally mandatory. One could of course say, in effect, “I am resigning from my moral offices of being a citizen of the world and a good steward of the environment to spend more time polluting the air and water, along with my little platoons of family, friends, like-thinkers, or fellow citizens of my country.” But that would not stop others from criticizing us on the grounds that we ought to—that we must—live up to the duties of the offices renounced. No one would say, upon hearing of our resignation: “That’s fine, you can go ahead and pollute and be as parochial as you like—it does no harm and is thus of no concern of ours.”

You can always be criticized for not upholding the duties of the office because your resignation (a means of self-disappointing) will never be accepted. The reason why is so other people or nations can say, “We all have a responsibility to certain norms; this is not optional.” To hold office in theory is not to be a source of self-legislation to the point that we, like absolute kings, are the law and can do as we please. To the extent that it is colored by liberal democratic suppositions, our modern version of appointment to political office, carries with it, ideally, the possibility of being unelected. But this rule does not apply to our common, tacitly held moral office.

If we simply cannot resign or be deposed from universal moral office (even if we undertake actions in apparent violation of that office) how is it that we are so acutely subject to “disappointment”? We can still be disappointed because the concept of appointment to an office as it relates to disappointment has receded in importance, while still functioning implicitly. At the same time, the language of feelings that arise from disappointments (understood in terms of once high, then fallen expectations) has increased. To feel disappointed is all that we need “rightly” to suffer a disappointment, and hence, to exercise our right to be disappointed.

What disappoints you? Are you, for example, still aiming not just to write well but, more foolishly, to be discovered as a good writer despite the fact that—disappointingly—your writing has been described with some accuracy as being aggressively unintelligible? Did your career in circus arts come up against insuperable obstacles due to your uncorrected myopia, your fear of heights, and your middle-agedness despite the fact that your acrobatic dreams remain undiluted? Your real disappointments may be less exaggerated and much more excruciating than those just sketched. I don’t know what they are.

How do we distinguish between the various modes of disappointment? Generally speaking, we don’t. We lack a theory of disappointment with which to clarify and complicate the question of disappointment as it pertains to death, life, and the slow-motion divorce between death and disappointment effected by modernity. There may be a moral psychology of disappointment and a literature as well. We shall briefly discuss the former first.

Disappointment and Moderate Distance

A number of porcupines huddled together for warmth on a cold day in winter; but, as they began to prick one another with their quills, they were obliged to disperse. However, the cold drove them together again, when just the same thing happened. At last, after many turns of huddling and dispersing, they discovered that they would be best off by remaining at a little distance from one another. In the same way the need of society drives the human porcupines together, only to be mutually repelled by the many prickly and disagreeable qualities of their nature. The moderate distance which they at last discover to be the only tolerable condition of intercourse, is the code of politeness and fine manners; and those who transgress it are roughly told—in the English phrase—to keep their distance. By this arrangement the mutual need of warmth is only very moderately satisfied; but then people do not get pricked. A man who has some heat in himself prefers to remain outside, where he will neither prick other people nor get pricked himself.—Arthur Schopenhauer

The porcupines have no king. They are a self-governing entity of sort, except that the only principle by which they are governed seems to be a need to escape the discomfort caused by the cold. Their means of governance are conventions, not laws.

The conditions under which they huddle together in the passage above, then, are ad hoc and unconstitutional. The solution at which they arrive to solve the problem of their mutual irritation is a provisional arrangement, promising only the partial, temporary satisfaction of the need for warmth, and some modest limitation of the capacity to disappoint and to be disappointed. As long as winter lasts, and they lack some inner source of heat sufficient to keep themselves alive on their own, they have little choice in the matter.

Necessity notwithstanding, the pressure of togetherness proves to be too much, given that each porcupine is equipped with quills to protect itself from its predators. The quill-equipped denizen of modernity has no means of treating a predator differently than it would a friend, of disarming itself, and being close in a way that does not incur the risk of social injury and subsequent disappointment.

Here, friends don’t disappoint but they are indistinguishable from enemies, as are family members from strangers; indeed, the very concepts of friendship and enmity, of family and strangers, are irrelevant in this context. Impersonal friction between generic individuals, however, is inevitable. Mutual pricking sets off a cycle of huddling in the hope of warmth and dispersing when that hope is disappointed, only to cease when the porcupines finally happen upon a way of being close enough to stay warm but not so close as to prick one another. Peace and relative relief from the pressure of potential disappointment is secured by polite distance rather than enhanced trust.

You disappoint people, and they disappoint you, so better to have as little business in common as possible. Democratic individualism lets people mind their own business. Through trial and error, prickly individuals, once conscious of the extent to which they are prone to disappointment, arrive at a rough modus vivendi, contingent upon the collective policing of boundaries.

Although Schopenhauer was not writing here of contemporary liberal democracy, we might, as a thought experiment, consider the ways, however limited, in which our own collective life is porcupine-like in aspect, and what, if anything, we might do about that. Schopenhauer himself did not need think about the choiceworthiness of political regimes as they pertain to the human propensity for hope and disappointment. To his mind, politically speaking, there is only one form of government, namely, monarchy “that is natural to mankind.” The problems of modern social life pertain to the masses of non-intellectuals, specifically, of non-philosophers. The people—the porcupines—are the poor, who live in the cold and search for warmth. In The Wisdom of Life, Schopenhauer remarks that whereas a philosopher, a man who is rich in himself, “is like a bright, warm, happy room at Christmastide, “ outside of that room, he suggests, “are the frost and snow of a December night.” The philosopher does not need to hope for warmth and to huddle with disappointingly nettlesome creatures to find it. He has his own source of heat.

For the philosopher, then, as well as those like him—the warm and happy people who are possessed of a rich inner life—modern life holds another option than that of frigid, crowded discomfort. Avoiding the clump of porcupines means staying inside the warm happy room of one’s mind and encountering the masses only if and when he opens the curtains and looks out a figurative window into the cold. “A man who has some heat in himself prefers to remain…where he will neither prick other people nor get pricked himself.”

The heat in question, Schopenhauer suggests elsewhere, is intellectual: the philosopher, with his capacity to warm himself, need not depend on others to kindle his thoughts. They can’t delight him and they can’t disappoint him. He is beyond their reach. To Schopenhauer’s mind, there is no connection between intellectual illumination and sociability, much less love. The pursuit of truth fosters the love of solitude, not of others. “A man’s sociability,” he suggests, “is roughly in inverse ratio to his intellectual worth; and ‘he is very unsociable’ is tantamount to saying ‘he is a man of great qualities.” For Schopenhauer, the philosopher enjoys a godlike isolation, reminiscent of the image of the theoretical life in Book 10 of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. The question of truth is best pursued at a remove from the world of give-and-take, or, as the fable would have it, prick-and-recoil. Truth falls outside the purview of the porcupines; even collectively, they cannot generate enough heat to shed light on anything.

Today, readers of Schopenhauer are relatively few. One need not, however, to have read him to feel—despite the fact that a life in which one has the leisure, skills, and material means sufficient to read and write philosophy means that someone, somewhere worked or is working at something presumably less pleasant to make that possible—that life precludes happiness across the board.

In the Schopenhauerian world, every expectation of happiness is a prelude to disappointment. In his words, “a man never is happy, but spends his whole life in striving after something which he thinks will make him so; he seldom attains his goal, and when he does, it is only to be disappointed; he is mostly shipwrecked in the end, and comes into harbor with mast and rigging gone.” Even if the desire to sail were to persist, the boat would not be able to go anywhere. Disappointment dictates the eventual abandonment of the open sea in favor of involuntary enclosedness and passivity.

A sense of disappointment does not bear with it any demands for action, and can lead, instead, to passivity, perhaps irritated by perseveration. On the face of it, one might think, not unreasonably, that it is intellectuals who are the most accomplished in transmuting disappointment into ponderous reflection upon its sources and ramifications, perhaps as a means of comforting themselves. Adolescents, however, may well rival them in this capacity, so heightened is their capacity for the felt experience of the yawning abyss between reality and one’s dreamlike half-expectation of what it could be. William Dean Howells is not wrong to remark that “The old are sometimes sad, on account of the sins and follies they have personally committed and know they will commit again, but for pure gloom—gloom positive, absolute, all but palpable—you must go to youth. That is not merely the time of disappointment, it is in itself disappointment; it is not what it expected to be.” In theory, the process of maturation should inevitably diminish the force of this discovery over time. In experience, sadly, it may not.

The university classroom, where intellectuals or their would-be equivalents meet up with the young, is the testing ground for the notion that one may become adept in the art of disappointment by virtue of being taught. For what do modern intellectuals, at least in the humanities, teach if not disappointment, and much more rarely, hope? Is it not the task of teachers to disabuse students of their illusions and pretensions to knowledge, and invite, in their place, the habits of critical thinking and the incessant asking of questions? In the Socratic vein, at least, teaching, at least metaphorically speaking, involves stinging your students like a torpedo fish, according to Plato, and, according to Socrates’s harshest critic, Aristophanes, stealing your students’ cloaks.

In Aristophanes' The Clouds, Socrates is accused of stealing a cloak, and although it is intended as a critique of his lack of respect for the law, I have always taken it to suggest a sort of compliment. A teacher is the person who shows you that the outer covering that you use to protect yourself from exposure to your own ignorance does not belong to you. That covering is woven out of the threads of other people's arguments, devices, and approaches. Thus, having your teacher steal your cloak is a matter of being dispossessed of what was never yours in the first place and, in the process, disappointed, perhaps acutely. It is painful to confront one’s own uncovered ignorance at the time. One feels thankful only later. Modern teachers less rarely face the temptation to become stealers of cloaks than they do to become merchants of hopes, on the one hand, or professional disappointers, on the other. The characteristic gesture of modern pedagogy (outside the natural sciences) belongs to Max Weber, who, in the first sentence of his lecture, announces that “This lecture, which I give at your request, will necessarily disappoint you in a number of ways.” He executes what he takes to be his duty while his listeners exercise their right—the right to be disappointed.

In liberal democracies, we derive the existence of the right to be disappointed from the supposition, as powerful as it is tacit, that we have both a right to feel happy. But for Weber, we also have the option of choosing heroically, if we are strong enough, to refuse the insipid and vain expectation of “happiness.” There is a deadlock between the pressure to exercise that right—which permits high expectations of happiness—and the pressure to refuse to exercise that right—which assumes that in this world of struggle there is no such right, and that only big babies believe in it.

We believe that if life does not console us, we have been wronged. Thus, we deserve to be disappointed and further, to give voice to our complaint. By a four-way cross-pollination of 1) the language of moral injury, 2) the language of rights, 3) the notion that we feel is what we ought to feel, and 4) the myth of a heroically tough-minded indifference to happiness, we have ended up with a peculiarly modern propensity and resistance to disappointment. Contemporary disappointment is morally fluid, as its literature shows (see, for example, the disappointed-because-idealistic-but-also-easily-duped stepparents in David Foster Wallace’s “Good Old Neon”). For a less-conflicted literature of disappointment, we must look back to the moment when both optimism and fear concerning the prospects of individualistic liberal democracy were at their height.

The Literature of Disappointment

I am thankful for small mercies. I compared notes with one of my friends who expect everything of the universe, and is disappointed when anything is less than the best, and I found that I begin at the other extreme, expecting nothing, and am always full of thanks for moderate good.—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Experience”

We find in Emerson the same notion that we find almost everywhere: high expectations issue forth in disappointment. Emerson associates the capacity to be easily disappointed with ingratitude for small blessings and moderate goods. Expecting everything is not a sign of great-mindedness. To his mind, however, life is unlike literature and philosophy in this respect. In those latter contexts, it is a bad thing for writers to be incapable of high expectations. They should not settle too easily for the humble, the practical, and the parochial over and against the universal, the fanciful, and elevated.

Modern authors disappoint him because their eyes do not, with fine frenzy rolling, glance from heaven to earth. Stolid, and too much given to counting costs and moderating expectations, they are ill-equipped to wheel with ease from high to low. Rather than wheeling and reeling with poised abandon, he suggests, modern British literature creaks. Its arthritic and mentally materialist mechanical gears move only in small, relentlessly predictable circles. There is no tension between high expectations of the universe, on the one hand, and the not so high realities of the hearth, street, and the neighborhood watering spot, on the other. Authors provide warm beer with no froth, and bread with no yeast or salt. Everything is locally sourced. That is not a promise but a problem. Emerson complains that:

“The essays, the fiction and the poetry of the day have…municipal limits. Dickens, with preternatural apprehension of the language of manners and the varieties of street life; with pathos and laughter, with patriotic and still enlarging generosity, writes London tracts. He is a painter of English details, like Hogarth; local and temporary in his tints and style, and local in his aims. Bulwer, an industrious writer, with occasional ability, is distinguished for his reverence of intellect as a temporality, and appeals to the worldly ambition of the student. His romances tend to fan these low flames. Their novelists despair of the heart. Thackeray finds that God has made no allowance for the poor thing in his universe,—more’s the pity, he thinks,—but ’t is not for us to be wiser; we must renounce ideals and accept London.”

Things were not always this way. From the Elizabethan to the Romantic period, Emerson opines, English poets trafficked in “the heights.” They breathed “diviner air.” Their capacity to reach those heights while still retaining what Emerson saw as a characteristically English preference for the low, sturdy, and homely produced amazement. The literature, preeminently that of Shakespeare, elevated readers. But by the time of Coleridge, something had broken. By that point, all that was left of the towering figures of the past were “stumps of vast trees in…exhausted soils.” The “fine arts,” Emerson laments, “fall to the ground.”

Coleridge marks the beginning of the end. The ghost of high expectations still loiters in his work, but it cannot be enticed back into taking up residence as the genius of the place:

“Coleridge, a catholic mind, with a hunger for ideas; with eyes looking before and after to the highest bards and sages, and who wrote and spoke the only high criticism in his time, is one of those who save England from the reproach of no longer possessing the capacity to appreciate what rarest wit the island has yielded. Yet the misfortune of his life, his vast attempts but most inadequate performings, failing to accomplish any one masterpiece,—seems to mark the closing of an era [my italics].”

When “vast attempts” aspire to but fall short of loftiness, we are in the landscape of disappointment. But disappointment, it turns out, is better than what follows, namely, a tolerance of and appetite for the vulgar and the low that never takes into account universal “heights.”

There is literature that disappoints. There is also the literature of disappointment, i.e., one that takes up disappointment as a theme and a style. For this, we turn to Anthony Trollope, for whom disappointment merits autobiographical and fictional attention. Given the collusion between disappointment and expectation, we might have expected that a full-blown literature of disappointment would likely be found amongst the most able exponents of grandiose expectations, the Victorian social optimists who promoted evolutionary progress. But this group did not include Trollope who, while not a pessimist, was measured at best with respect to the prospects of relieving the human estate through progress. No one who experienced the cruelty with which he was treated as a schoolboy could retain a sanguine belief in the perfectibility of humankind. In contrast to the deep wounds to his soul that he received as a child, the disappointments of the writing life, though difficult, were nothing compared to the damage that had already been done.

So skilled is Trollope in the capacity to go numb, familiar to those who have been abused, that one may read his treatment of disappointment, both in his autobiography as well as in his fiction, as an attempt to imagine what the blows of disappointment would feel like to a person not previously numbed, for the purpose of mere survival, to much worse. His autobiographical account of the sorry fate of his first novel offers an example of the studied, uneasy way in which he treats disappointment.

“Mr. Newby of Mortimer Street was to publish the book. It was to be printed at his expense, and he was to give me half the profits. Half the profits! Many a young author expects much from such an undertaking. I can with truth declare that I expected nothing. And I got nothing. Nor did I expect fame, or even acknowledgment. I was sure that the book would fail, and it did fail most absolutely. I never heard of a person reading it in those days. If there was any notice taken of it by any critic of the day, I did not see it. I never asked any questions about it, or wrote a single letter on the subject to the publisher. I have Mr. Newby's agreement with me, in duplicate, and one or two preliminary notes; but beyond that I did not have a word from Mr. Newby. I am sure that he did not wrong me in that he paid me nothing. It is probable that he did not sell fifty copies of the work;—but of what he did sell he gave me no account."

I do not remember that I felt in any way disappointed or hurt. I am quite sure that no word of complaint passed my lips.”

We are told that what the high expectations of most young authors are in such situations. His own lack of expectations is lent emphasis: rather than saying, “I expected nothing, and I got nothing,” we are assured that “I can with truth declare that I expected nothing,” as if he were testifying to the matter before a court and needed to use such nice wording as to provide a way out if needed. To say that one “can with truth declare” that one expected nothing is ever so slightly different than saying that one actually did expect nothing.” Indeed, as a fictional character in Trollope’s novel The Bertrams observes, “Let any of us…convince with ever so much firmness that we shall fail, yet we are hardly the less downhearted when the failure comes.”

Most of the first paragraph in the passage quoted from Trollope’s autobiography seems to consist of a not especially convincing attempt to convince himself that his younger self had been so certain of failure that the blow, when it came, scarcely registered. The sentence that begins the next paragraph lends further doubtfulness to his insistence that he expected nothing and thus was not sorry to have received nothing: “I do not remember that I felt in any way disappointed or hurt. I am quite sure that no word of complaint passed my lips.” Again we find the legalistic attempt to carve out distance from a clear claim concerning his degree of disappointment.

“I do not remember” is a classic dodge. More interesting is the subsequent claim “that I felt in any way disappointed.” Does the feeling of disappointment arising from dashed hopes (even irrational ones, against the entertainment of which we had sternly warned ourselves) admit for such fine distinctions that one may determine the particular “way” in which one was disappointed or not disappointed? Why the emphasis on “in any way,” as distinguished from simply “disappointed”? He is not merely certain that a word of complaint passed his lips but quite certain. The caprices of memory aside, if his lack of disappointment was that certain, would there have been any question as to his silence concerning a feeling that was never felt?

How Disappointing People Live Now

We may lead lives of noisy disappointment rather than quiet desperation. Flattened, downcast, and low sensibilities may be strong enough to drive one to drink—thereby, inducing further depths still—but perhaps not to stop one from hoping for impossible things. Reality is recalcitrant and will not mold itself according to our highest hopes. Because of this recalcitrance, hopes beget their dashed progeny, who gape at them from the ground. While hope connotes buoyancy and looking up—everything to do with the air and sky and mountains—disappointment follows from a surrender to gravity or even an exercise of force resulting in a plunge to the valley.

We are both buoyant and sinking, both parachuters and parachutes, life preservers and the weight that they bear—lurchers back and forth; bobbers-up and down in the water, or, in the terminology of Stevie Smith, wavers and drowners:

Poor chap, he always loved larking

And now he’s dead

It must have been too cold for him his heart gave way,

They said.

Oh, no no no, it was too cold always

(Still the dead one lay moaning)

I was much too far out all my life

And not waving but drowning.

Disappointed people are drowners who love larking—unsafe walkers down train tracks in search of a late December diversion, something akin to a rush of warmth in the cold. One imagines it was not all that it was cracked up to be, whatever it was that they got out of the experience. Who knows what obscure satisfaction they sought. One imagines it was emotional. But while other people are contagious to us, proximity may required to catch certain feelings. Regarding the walkers down the tracks, who would want to walk closely enough by that pair to the point that one might share the risk or the hope of whatever it was they were seeking in setting out on such a path? Risking your life would hardly be worth it to know what they felt.

Though mostly dust, we are not dead quite yet, nor would we be so. Neither are we ghosts. Life is a prerequisite for what we feel. We disappoint, therefore, we are. Hope-killing, disappointing, yet ever hopeful, promising compounds of body and soul.